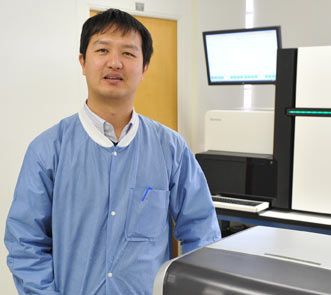

Funding from state taxpayers helped Lei Zhang, a researcher with the UCLA School of Dentistry, get the state-of-the-art equipment he needs in his quest to develop a more accurate, less costly and less invasive test for breast cancer.

Zhang, an assistant researcher in the Section of Oral Biology at the UCLA School of Dentistry, is devising a test for two forms of ductal carcinoma.

And he’s doing it with the help of donations from state tax filers, who have checked off a box on their state tax forms to support the University of California’s California Breast Cancer Research Program. With funding from California taxpayers, studies, such as Zhang’s, have led to simple tests that guide treatment by distinguishing non-invasive forms of the cancer from aggressive types.

Breast cancer research is only one of two causes state taxpayers can donate to by checking off a box on their tax form. While checking line 405 will enable taxpayers to contribute to research for breast cancer, checking line 413 is a way to designate funding for the California Cancer Research Fund, which supports lung cancer screening. Both funds are administered by two UC programs that are renowned for innovative research and helping cancer patients and families, especially the underserved. In 2012, the two funds received a combined $873,000. Contributions from 2012 state tax filers averaged about $14.

Someday, thanks to Zhang’s work, breast cancer screening may be done by looking for biomarkers in human saliva — just about the least invasive way to access genetic material.

Before seeking support from the program, his team developed panels of biomarkers in saliva to detect pancreatic and lung cancer, using the laboratory workhorse of DNA and RNA screening technology called a microarray. This powerful and widely used strategy allows researchers to compare snippets of patients’ DNA or RNA with similar genetic material in healthy people. Where the gene sequences or gene expression levels differ can be a clue to a cause of disease.

But Zhang wants to move from detecting partial genes to actually sequencing entire genes using a state-of-the-art technology called "Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)," an approach that promises more accuracy.

One of the commercially developed screening tools he will use offers major advantages over microarray approaches. It detects panels of cancer-related genes very quickly, is easy to employ and provides the needed genetic evidence at low cost.  "We hypothesize that all molecules of the body are affected by primary tumor," Zhang said. "The tumors will stimulate changes in DNA and RNA throughout the body."

"We hypothesize that all molecules of the body are affected by primary tumor," Zhang said. "The tumors will stimulate changes in DNA and RNA throughout the body."

Zhang watches a colleague use a Next Generation Sequencing machine.

He suspects that using the new sequencing approach to screen for cancers will significantly boost accuracy, and reduce both the time and cost needed to get results.

"CBCRP (the California Breast Cancer Research Program) has funded our studies at exactly the right time because we were really struggling to develop novel and accurate biomarkers based on NGS," Zhang said. "We needed support to push the research and evaluate its effectiveness."

Zhang hopes the funding will advance the new strategy to the point where the National Cancer Institute will support large-scale clinical trials. He expects NGS will be available for breast cancer diagnosis in clinics within five years.

Zhang feels grateful for the willingness — even eagerness — of breast cancer survivors to participate in the studies, providing saliva samples needed to confirm the tests’ effectiveness.

"I have been very touched by the many survivors who want to support this work. They have suffered, and they want new research to benefit other women."

_____________________________________________________________

See the list of grants that have been funded through breast cancer research contributions to line 405.